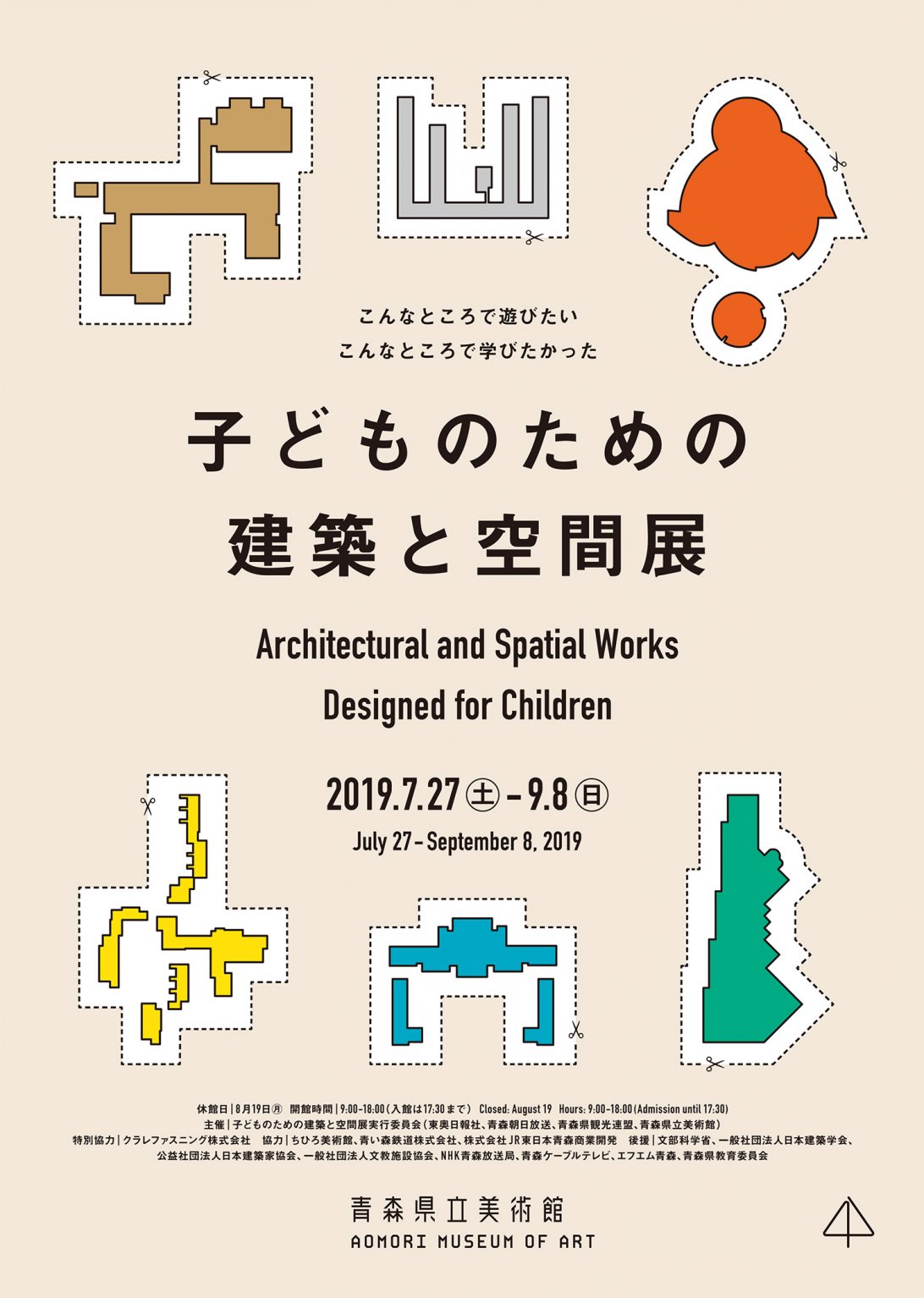

Architectural and Spatial Works Designed for Children

The places that people spend time in when they are children deeply embed themselves into their memories, influencing the identities and lifestyles that they establish later in life. This exhibition presents masterful examples of modern Japanese buildings and spaces designed for play and study—the two primary activities of childhood. A variety of playground equipment, toys, and picture books created by artists and designers will also be displayed.

Details

Dates

July. 27 – September. 8, 2019

Closed

August. 19

Hours

9 a.m. – 6 p.m. (Admittance until 5:30 p.m.)

Admission

Adults: 1,500yen(1,300yen)

Senior High School and University Students: 1,000 yen (800 yen)

Elementary and Junior High School Students: Free

Admission

Lawson Ticket (L Code 21378), 7 Ticket, Pomit Ticket, and other ticketing agents in Aomori. *Sold until July 26.

Aomori City: Sunroad Aomori, Narita Honten Shinmachi Store, Sakurano Department Store, 11 Co-op stores, Prefectural Office Co-op (North Building 1st Floor, East Building 1st Floor), Hamanasu Hall (Aomori Municipal Labor Mutual Aid Society), Aomori Tourist Information Center ASPAM 1st Floor Information Counter, Linkstation Hall Aomori, Gala Town Aomori West Mall, Aomori Museum of Art Museum Shop, Aomori Museum of Art 1st Floor Information Counter

Hirosaki City: Sakurano Department Store, Hirosaki University Co-op, Nakasan, Hiroro

Goshogawara City: Elm-no-Machi Shopping Center

Hachinohe City: Sakurano Department Store, Nakago Miharuya, Lapia, Hachinohe Portal Museum “hacchi”

Mutsu City: Maeda

Exhibition Structure

Section I

The Late 19th Century and the Dawn of Spaces for Children

The establishment of the Gakusei education system in 1872, as well as the passage of the Kaisei Kyoikurei (“Revised educational ordinance”) seven years later, led to Japan’s first compulsory primary education system. Featured in this section is the Kaichi School (1896; Seiju Tateishi). Its mock Western style symbolizes the Western-influenced political and social changes that occurred in 19th century Japan. Also on display are educational materials and tools that were created to accommodate what was, at the time, an entirely new approach to education: one teacher instructing a large group of children in the same setting. The construction of primary schools helped propagate children’s education in Japan, while mechanical rides displayed at expositions offered new forms of children’s play.

Section II

The Early 20th Century and the Discovery of Children’s Worlds

This section highlights schools such as the Jiyu Gakuen Girls’ School (1921; Frank Lloyd Wright and Arata Endo) that represent the 1920s effort towards more liberal education systems, inspired by the democracy movement that prevailed in Japan during this time. However, there are also displays related to steel-reinforced concrete schools, which were built in the wake of the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 in order to provide a more earthquake- and fire-resistant educational environment. Increasing commercialism and consumerism led to the propagation of child-centered design in products, homes, and lifestyles. This trend is exemplified by Akai Tori (“Red bird”), a magazine dedicated to children’s literature. Original artwork from this magazine is also on display in this section.

Intermission

The Flowers that Bloomed on the Eve of War

Japan’s heavy industries grew rapidly in the 1930s. It was during this period that the country experienced a boom in schools featuring International style modern designs, such as the private Keio Gijuku Yochisha (1937; Yoshiro Taniguchi). Another example featured here is the public Takanoguchi Primary School in Hashimoto, Wakayama Prefecture (1937; Hoichi Yabumoto). Despite this economic growth, it was a politically unstable time in Japan just before the wartime, and children found comfort in literature magazines and other items that are on display in this section.

Section III

1950 – 1970: The Coming of a New Era, Creating a World of Children’s Dreams

The postwar period in Japan was one of dramatic change as the country rebuilt itself and experienced rapid economic growth. Schools were increasingly designed from a scientific perspective, while a number of amusement parks were built from the late 1950s onwards to accommodate the increased leisure time of the Japanese. This section introduces visitors to children’s environments that represent these trends, such as the public Yakumo Primary School Branch Campus (1955; present-day Miyamae Primary School) in Meguro Ward, Tokyo, and Kodomo no Kuni (1965), an outdoor theme park designed by Metabolist architect Yukio Otani and Japanese American sculptor Isamu Noguchi.

Section IV

1971 – 1985: Chatterboxes, Pranksters, and Adventurers in an Age of Diversity and Individualism

This period saw the emergence of experimental schools that, inspired by open classroom concepts borrowed from the US, removed grade and homeroom barriers to provide children with a more liberal environment in which to nurture their individuality. This section introduces a few of these schools, such as Katoh Gakuen Gyoshu Elementary School (1972; Maki and Associates) and Miyashiro Kasahara Elementary School (1982; Atelier Zo). There are also displays related to the work of Nobuko Ogawa, who strongly believed in the potential of children and who created spaces for them that were scientific in design while still being grounded in children’s habits and interests.

Section V

1987 and Onwards: For the Children of Today and Tomorrow

Beginning in 1985, school construction projects increasingly employed the services of architects to design spaces that were more conducive to new methods of study. The goal was to provide a richer lifestyle for children that would allow them to truly shine. This section introduces select examples of this trend, and the public Miyanomori Primary School (2016; Sakari Sogo Plan and Coelacanth K&H Architects) in Higashi-Matsushima, Miyagi Prefecture. The latter was built in an area that was devastated by the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, and is intended to serve as a symbol of hope for both children and adults living there. Also on display are materials related to projects designed to reverse the current trend of dwindling spaces and opportunities for children’s play—a consequence of the dramatically changing social and urban landscape of Japan.