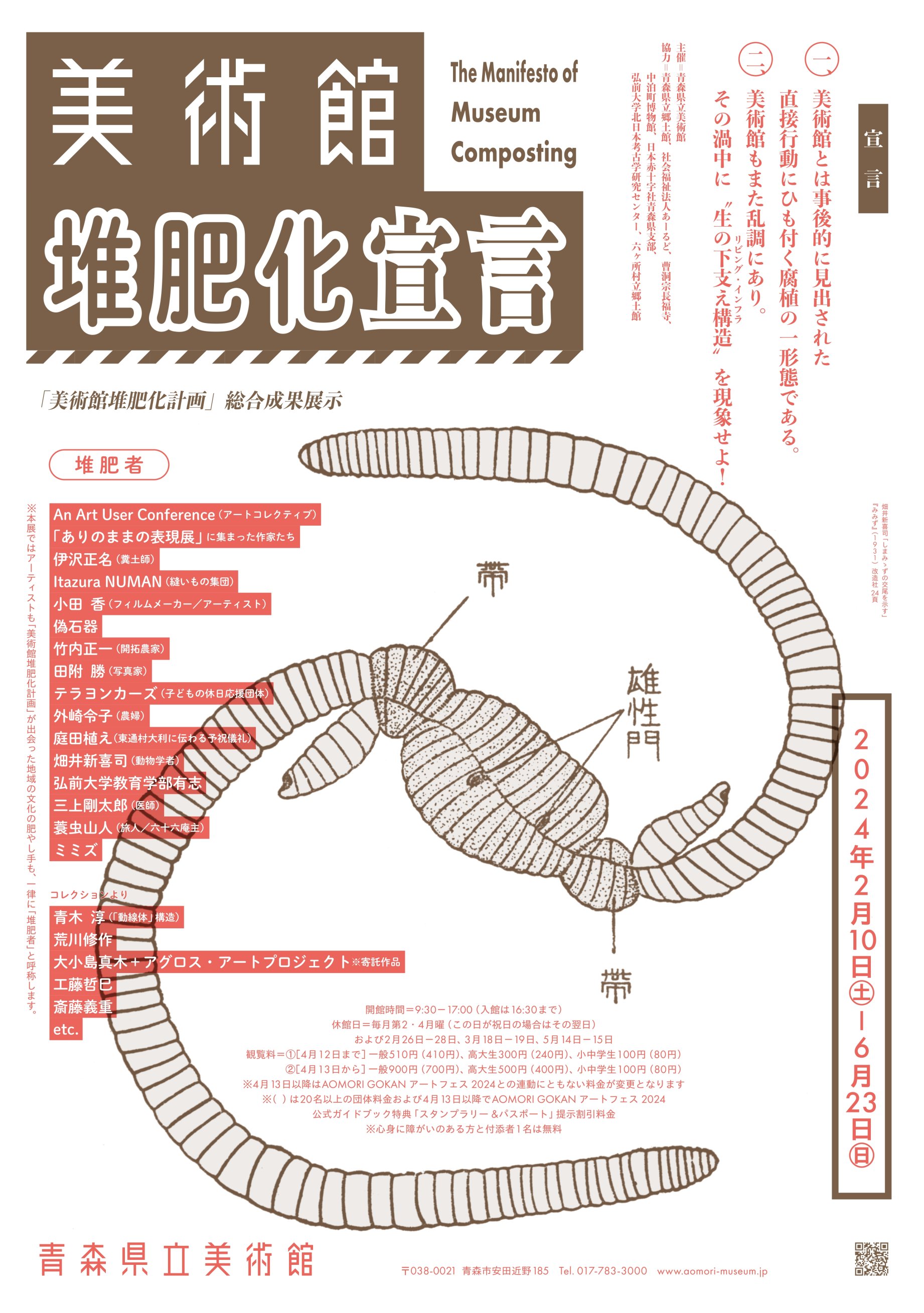

The Manifesto of Museum Composting

1. Museum is a form of humus tied to a direct action found after the fact.

2. Like beauty, Museum is also in disarray. Launch 'Living Infrastructure' in the middle of this vortex!

Aomori Museum of Art is pleased to present the special collections exhibition “The Manifesto of Museum Composting.” This exhibition is a comprehensive showcase of the “Museum Composting Project,” undertaken between 2021 and 2023 in various areas throughout Aomori Prefecture.

“Museum Composting Project” was conceived with the aim of enriching local cultures, and the museum collaborated with participating artists to discover and introduce the appeal of different regions throughout Aomori Prefecture. The exhibition, consisting of seven manifestoes (sections) derived from these outcomes, showcases the activities of those collectively regarded as “composters.” This group includes artists and individuals encountered through the project who have contributed to community enrichment through unique methods like welfare-based initiatives, afterschool programs for kids, and museum concepts. It also encompasses ethnic rites, earthworms, and natural stones, all viewed equally as “composters.” Their efforts are woven together with items from the museum’s collection and related initiatives. The exhibition, a result of the collective efforts of the composters, who—by banding together and occasionally clashing with each other—quietly challenge the traditional power structures of the art institution that aim to tether us all to art. By inducing gentle dysfunction, it paves the way for us to reimagine the museum as a space that is truly inclusive, opening up possibilities for us to use the museum more equitably. Therefore, the exhibition declares the decomposition and regeneration of the museum as our “living infrastructure,” a space to support and strengthen our lives in the face of increasing stagnation and confusion in today’s physical world.

Details

Exhibition period

February. 10 – June. 23, 2024

Closing day

Every 2nd and 4th Monday of month and May. 14-15, 2024

Venue

N,O,P,Q,M,L,J,I,H etc.

Composters

An Art User Conference, Bare Expressions, IZAWA Masana, Itazura NUMAN, ODA Kaori, Fake stone tool, TAKEUCHI Shoichi, TATSUKI Masaru, tera4WDs, TONOSAKI Reiko, pre-harvest ceremony in Ori (village of Higashidori), HATAI Shinkishi, Students of Hirosaki University, MIKAMI Gotaro, Bagworm Hermit, earthworm etc.

[from COLLECTION]

AOKI Jun, ARAKAWA Shusaku, OHKOJIMA Maki+Agros Art Project, KUDO Tetsumi, SAITO Yoshishige

Organizers etc.

Organizers

Aomori Museum of Art

Exhibit cooperation

Aomori Prefectural Museum, social welfare corporation AORLD, Chofukuji temple, Nakadomari Museum, Japanese Red Cross Society in Aomori, Archaeological Research Center for Northern Japan, Hirosaki University, Rokkasho Museum

Admission

Ticket

Adults -900yen(700yen)

Students(high school students and college students) -500yen(400yen)

Children(Junior high school students and under) -100yen(80yen)

Admission is free for disability passbook holders and up to one accompanying adult.

Exhibition Structure

Manifesto 1 Bagworm Hermit: From collection to sharing

A museum does not exist a priori; it stands in response to the times.

This quote is taken from the essay “Myujiamu = Bokyaku No Kikai” [Museum = Opportunity of Oblivion] by Aomori-born playwright TERAYAMA Shuji. The essay first appeared in the November 1981 issue of the Japanese art magazine Bijutsu Techo. Terayama’s assertion, based on retrospective thinking, prompted the museum to diverge or project into the infinite past. In retrospect, that may have been a museum—it has become impossible to discuss a museum only in the narrative of its development. Museums are ubiquitous, parallel frameworks—liberated from the constraints of time. Their use is always open for review and change. “The Manifesto of Museum Composting” explores the museum by retracing the path of traveling artist MINOMUSHI Sanjin (Bagworm Hermit / 1836–1900) and his conception of Mutsu-an.

Minomushi, whose lifelong ambition was to build Rokuju Roku An (Sixty-six Hermitages), a group of buildings that house and display old earthenware and unusual objects from across Japan, was an early practitioner of what we call museums today. While undertaking the “Museum Composting Project 2022”, Aomori Museum of Art had the opportunity to study the works left behind by the artist in Aomori Prefecture. He communicated with many people with the aim to create Mutsu-an, one of the Sixty-six Hermitages, which collects and displays various materials associated with Aomori Prefecture. As outcomes of this research, this section presents Minomushi’s paintings depicting archaeological artifacts seen and heard in various parts of the prefecture, along with those artifacts, which were first collected by historian SATO Shitomi, an old acquaintance of Minomushi, later added to the collection of Aomori-based doctor NARITA Hikoe, and are now housed in the Hirosaki University’s collection. Sketches of earthen figures treasured by Minomushi, drawn by Sato, are also on display.

Minomushi visited collectors around the prefecture, asking them to show him the treasures they owned. One can quite easily imagine the suspicious look on their faces. Minomushi depicted in his paintings what collectors kindly showed him or told him about and left the paintings to the community. He said that he would come back if necessary but passed away before he could ever return. Now, who do these works belong to? In fact, taking such an equivocal attitude toward the idea of ownership may possibly affect how artworks would be passed down to the next generation. His works would be taken care of by the community until the day Mutsu-an opens. At the same time, everyone should have access to those works, as they cannot be owned exclusively by the artist or collectors. When works of art are shared between people, the conflict between preservation and exhibition can be overcome. When the artworks finally gather at Mutsu-an—a museum—it becomes a space for cultivating the future of the community by utilizing the past as a source of enrichment.

Today’s museums collect works and preserve them in storage to protect them from material damage. Mutsuan, which yet to be realized, shares works to protect hopes preserved in them. Discovering the buds of a future museum between these two ridges seems essential for finding common ground where we can coexist with others in a community, and for strengthening the roots under places where art is allowed to flourish.

Manifesto 2 Behind the droppings

When we are at the zoo watching the hippos or elephants, standing there on the other side of the cage, the animals may suddenly defecate without warning. Sure, it’s gross, but I’m oddly fascinated by the sight—am I the only one? As the saying goes, “When you’ve got to go, you’ve got to go”, but art museums and other modern facilities have long resisted the laws of nature, considering the prevention of leaks or droppings as their duty. It is indeed essential to maintain electrical and drainage systems to ensure the safety of both artworks and visitors. When we consider our world, marked by frequent disasters, we cannot help but feel slightly anxious, picturing ourselves dependent on technological systems that could deny us access to fundamental needs like water or sanitation without electricity. So, who is really trapped inside the cage—animals or us? Art museums need to reinvent themselves in light of what is happening outside the confines of their cage. It’s inevitable to be captivated by the sight of animals defecating so unapologetically. You could even say it’s an expression of their natural liberty, don’t you think?

It seems we have forgotten the possibilities of leakage…

This quote is taken from the text “More Ni Tsuite: Chokko To Shiteno Shoku” [About Droppings: Food as Direct Cultivation] by agricultural historian FUJIHARA Tatsushi (1976–). Fujihara’s vision, intertwined with the thoughts of Hachinohe-based thinker ANDO Shoeki, seeks to explore the significance of leakage, attempting to reach the source of life and the world of self-determination and autonomy. His vision prompts us to reconsider “leakage” in its many forms, such as the ecological practice of IZAWA Masana, who, for over fifty years, has stopped using toilets in favor of relieving himself outdoors. When the “Museum Composting Project” was conceived, we invited Izawa as a guest lecturer for the “Museum Composting Project 2021” to gain ideas on how to open up the approach to artworks and museums and become aware of the natural world outside of the museum. Meanwhile, during the “Agros Art Project 2017–18: Tomorrow’s Harvest” at Aomori Museum of Art, some participants discontinued rice farming and artmaking altogether, returning to their usual lives with confidence in what they do. This could also be interpreted as another example of “leakage.”

This section presents the work of Izawa, whose photos taken between 2007 and 2009 document how his own excrement, like compost, decomposes in nature and supports the life of other organisms. This work is presented alongside Tomorrow’s Harvest, a large-scale painting created during the Agros Art Project by OHKOJIMA Maki and participants, who questioned the relationship between people, society, and nature in the process. The museum, in response to these works, presents “models of social critiques”, which were produced in the 1970s by KUDO Tetsumi, a prominent figure of the Japanese Anti-Art movement. Rice has long sustained Japanese society. Izawa says, the character for “droppings (糞)” exists with “rice (米)” in the field. This section overlays the function of feces—”dropped” from the human body, derived from rice, in a cycle between living organisms and microorganisms—onto artworks. It asserts that artworks are inseparably linked to our lives beyond being mere products of the art system, encouraging an visionary practice that envisions museums as fields of energy (compost sites) linking our lives to the next generation.

Manifesto 3 Composters between us

In previous sections, we shifted the ideal form of the museum based on the idea of sharing, transforming our perception and handling of artworks to something akin to compost, which sustains life. Gazing beyond the museum and artworks as they “drop” through the museum walls and out into the community, the possibilities for collection appear boundless. The curator, unable to bear it any longer, ventured out of the museum. Through their eyes, everything appears to insist on being regarded as a work of art. Is the curator under the impression that they can collect everything under the sun? What an arrogant gaze—so typical of curators!

Nonetheless, when we strip away this filter of “collecting” and confront the reality of the community in earnest, things that were obscured from view within the museum come into focus. Activities and creations function in a way that they become connected to the circumstances of their surroundings, like compost supporting local growth. Anchored on such principles, art intertwines with our society and environment, and only then does the autonomous value of art resurface. What emerges beyond this is the prospect for museums to reimagine themselves as spaces where the act of creation can be recontextualized within a broader, raw context. Considering these issues, the “Manifesto” exhibition has chosen to refer to all individuals who reside, produce, and express themselves in the community—regardless of whether they call themselves artists—as “composters” and to showcase their work and activities.

In this section, we feature the film Homo Mobilitas by filmmaker and artist ODA Kaori, who has participated in the “Museum Composting Project” for the past three years. TAKEUCHI Shoichi, a settler farmer from Nakadomari (formerly known as Nakasato) who worked on the post-war Jusanko Lake reclamation project; photographs by the farmer’s wife, TONOSAKI Reiko, capturing the shifts in lifestyle from the Heisei to Reiwa era in the Miyanosawa area of Nakadomari. Lastly, we introduce initiatives involving mini 4WD model cars by the Chofuku-ji based “Children’s Weekend Support Group” tera4WDs, who we encountered during the “Museum Composting Project 2023” in the village of Sai. This section attempts to expand the museum as a space by incorporating the countless activities of composters who actively nurture and shape the rich fabric of the community.

Manifesto 4 TATSUKI Masaru: Engraving land / Me

TATSUKI Masaru, who participated in the “Museum Composting Project 2022”, is a photographer whose practice is driven by aspects often overlooked by history and society. In 2022, Tatsuki visited Rokkasho Village, and with the support of Rokkasho Museum, the artist photographed earthenware fragments preserved by local historian NIHONYANAGI Shoichi, creating new photographic works for a series titled “KAKERA”. These pieces, unearthed during large-scale development in the 1960s, were wrapped by Nihonyanagi in sheets of contemporaneous newspaper. That year, Tatsuki organized a photography exhibition titled “Engraving land”, which took place in the permanent exhibition room of Rokkasho Museum and an underground storage area for earthenware fragments. The exhibition included photographs of the village scenery today, as well as images of the stone monument recalling the mass relocation of settlements following the large-scale post-war development. Throughout his continued visits to the village, Tatsuki conceived the idea of photographing lunch scenes with people who reside and gather from both inside and outside the village for work, resulting in the piece “Lunchtime”. In this section, we present an exhibition conceived by the artist himself, comprising interviews with collaborators who participated in Lunchtime, where they were asked about ideas of wealth and poverty. Additionally, selected works from the exhibition “Engraving land” are featured, alongside an excerpt from the “New Comprehensive National Development Plan (Economic Planning Agency, 1969)”, which served as the basis for development.

Due to the difficulty in accessing the land set aside for development, the village of Rokkasho was forced to level its terrain and bury its history. The exhibition “Engraving land” tries to foster a mindset among Tatsuki, the villagers, and, above all, the viewers, enabling them to individually recount history through their engagement with the ordinary fragments that once pieced together the village. At first, the photographic subject was earthenware created through firing, and then it later expanded to live and fresh lunches arranged on (earthen)ware. Over the course of two years of production, Tatsuki seeks to reveal the time that has been or is being engraved into the village, challenging the superficial gaze directed towards Rokkasho. The excavated earthenware embodies a past transitioning into the present, while the act of dining reflects the future taking shape in the present-day village. By combining the series “KAKERA” and the work Lunchtime, the village’s historical structure is rewoven, revealing a complex present that is connected to our own. This section weaves together the residents’ experiences of time passing in Rokkasho with Tatsuki’s perspective. It makes something that had previously looked far away more real, enabling the artist to depict a place that is linked to our individual experiences in the present.

Finally, we would like to express our sincere gratitude to everyone who cooperated in the production of Lunchtime, companies that expressed their interest, and Rokkasho Museum Director, Mr. Suzuki, and all museum staff members who have supported the production over the past two years.

Manifesto 5 Practice for Com-post humanities

Compost typically refers to the accumulation of organic matter that has been broken down by microorganisms in the soil (the residue that remains after decomposition is called “humus”). It can be recognized as compost only when it proves its effects, such as combining with substances in the soil and helping plants grow roots. In essence, compost does not refer to a particular form; rather, it refers to the workings that are subsequently discovered, and there are parallels between compost and the workings of society, which changes as we coexist. Perhaps living together is like composting itself—an iterative exploration to find the ideal distance between disparate beings as they ebb and flow. And when we approach this iteration through an inclusive lens, we realize that there is a pathway toward an autonomous and harmonious society. We learned this in the “Museum Composting Project 2021” with AORLD, a social welfare organization that aims to enrich communities by centering people with disabilities; and from the “Museum Composting Project 2023” with Kandachime horses, a native breed that has lived vigorously in harmony with humans for over 300 years on Cape Shiriya in the village of Higashidori.

This section presents recently exhibited works from the “Arinomama no Hyogen” [Bare Expression] exhibition, a project hosted by AORLD to promote the artistic and cultural activities of people with disabilities; a painting created in 2021 by volunteers from Hirosaki University’s Faculty of Education, based on their experiences at AORLD’s guest house and welfare space “colere-ON”; ODA Kaori’s film which captured everyday scenes of AORLD in 2021; and other works by Oda comprising mainly of video work, using Kandachime horses as motifs. The works on view from the exhibition “Arinomama no Hyogen” [Bare Expression] have been selected by Oda and the curator of this exhibition, with the cooperation of AORLD. These works dare to emphasize how processes of selecting and being selected determine the course of each life, and how these processes have standardized power structures. This section also attempts to break down the two-tiered power structure between museums and artists by introducing a third-person perspective through audience intervention. It is our hope to transform the museum into a space that inspires us to seek a society that supports individual autonomy alongside communal living.

In a world fraught with conflict and contradiction, is it possible to create a space that redefines the distance for coexisting across species? This section presents how the museum engages with this theme through the initiatives of the social welfare organization and the presence of native Japanese horses, exploring and reflecting on them through diverse practices.

Manifesto 6 An Art User Conference: General Museum | Graves

An Art User Conference (AUC) is an anonymous collective that reimagines the division of labor in art—including artists, critics, and curators—from the standpoint of the user, striving to forge new art spaces. AUC has participated in the “Museum Composting Project” for three years running, undertaking their project “General Museum | Graves” in various sites, including the outdoor environment of Goshogawara and the landscape of the Tsugaru Railway in 2021; Kirisuto no Sato (Christ’s Hometown) in Shingo in 2022; and the ruins of the Oma Railway Memorial Road in Kazamaura in 2023.

“General Museum” considers the environmental world from a general viewpoint and approaches the museum as a “new public sphere” through its exhibitions, activities, and online presentations. The title “General Museum | Graves” (hereinafter “GM | Grave”) takes its inspiration from Aomori’s association with ruins and sacred sites, which are notably present throughout the prefecture. As part of their ongoing exploration of museums entering real spaces, signboards resembling road signs were installed at the aforementioned sites, inviting viewers to visit different sites while communicating with the space.

After three years of wriggling between imagination and reality like an earthworm—eating and excreting soil to fertilize the Earth—”GM | Grave” has now been developed in the museum’s exhibition room, pushing our perception into perpetual thought and imagination. The world that extends beyond the confines of the museum—the cityscape, sea, universe, and the afterlife—and objects that can be perceived from those points are projected onto the walls. On another wall, graphite, coral, bullets, fragments of earthenware, and more are embedded. These objects reveal the geological-geopolitical circumstances surrounding our museum: traces of meteorites that have fallen to Earth since its formation; that this place was once underwater ten million years ago; that the Jomon people inhabited it 6,000 years ago; and that it now lies next to a military base of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces. By using the traits of the contemporary art museum—which can cancel the continuity of time and space in reality—a new distance is found between imagination and reality, and with this distance, the project attempts to grasp the world in more “general” ways.

Tombs offers a slightly different perspective on the world. I don’t belong in that world anymore, but I’m not entirely removed from it, either. There is some distance there, and that distance should give you an opportunity to view the world more comprehensively.

This passage by AUC should be taken seriously by those who have come to live in the post-modern world by burying God and History with a capital “H,” as it serves as a declaration to use the museum as a space to accept death as one accepts life.

Manifesto 7 Here is the museum as "Living infrastructure"

Minomushi Sanjin’s Mutsuan. Droppings, rice, ecology. Documenting development and daily life. Movement. Children’s holiday clubs. Lunches in the village. Disability-focused community development. Education. Gathering and dispersing. Kandachime horses. “General Museum”. Earthworms. Over a period of three years, the “Museum Composting Project” facilitated the decomposition and transformation of the museum as a compost site through encounters with “composters” —individuals and collectives who sustain and drive action in the real world.

To conclude this exhibition, we will propose tangible approaches to presenting works in the museum-turned-compost site. The intermingling of artworks—those displayed with those still in their boxes—captures the state of pre-exhibition, where pieces are concealed even as they are revealed. The artworks that circumvent this limbo (or death) are anticipated to re-emerge as the composting forces that perpetuate life. The hand-sewn Red Cross flag by MIKAMI Gotaro, a medical doctor from the village of Sai, which functioned as a lifeline for wounded soldiers during the Russo-Japanese War, serves as a starting point transcending time and space. The video work of this year’s Niwa-taue, a pre-harvest ceremony in Ori, in the village of Higashidori, is borrowed, collected, and documented in support of the statement. From the museum collection, SAITO Yoshishige’s two-dimensional work TREEAIZ, constructed from assembled wood planks, and ARAKAWA Shusaku’s Work, which resembles industrial waste, is the humus-like residue presented by the current museum.

The main feature of this section is the work of the sewing collective Itazura NUMAN. NUMAN, which participated in the “Museum Composting Project 2023,” collected secondhand clothing and fabrics with the help of the local community. Turning these fabric scraps into handicrafts, NUMAN exhibited these pieces at the Maeda Department Store in Mutsu and at Kaneshichi+, an old kominka house in the village of Sai. The project “Meddlesome” was also held in conjunction with workshops to present and redistribute the works to the local community. NUMAN’s work, an expression of an offbeat form of direct democracy, offers a line of defiance to the oppressive realities of work linked to power dynamics. It symbolizes our efforts to recapture the intrinsic joy and creativity of labor and reflects the self-healing process within it. Like their work in the Shimokita Peninsula, NUMAN’s artistic initiatives in this section embody a kind of “joyful democracy”. They are a prelude to celebrating the practice of “living together”, weaving a path from Shimokita to the museum and beyond.

Museum as compost. Fundamentally, it serves as a place where objects converge to form a fertile environment, where the act of viewing encourages individuals to reshape their lives and infuse new insights into their daily routines. As we conclude the “Manifesto of Museum Composting” exhibition, we hope that the museum will celebrate its own transformation, using this exhibition to anticipate its evolution into a form of living infrastructure where compositing practices can thrive.